Crazy concepting

With now our three approaches and accompanying research questions clearly defined, the brainstorming for ideas finally could kick off. As highlighted in the previous blog, we tried to focus on the short-term project, finding a solution to facilitate informal reporting of sexual harassment in a physical space while ensuring institutional linkages.

We found out from interviews with experts and via reports that there is a big lack of data on sexual harassment. But it is not that there is no research being done on this problem. On the contrary. There is no data because there simply is no reporting of cases. Biggest reasons for this phenomenon are the flawed legal system for reporting, the painful procedures or the misogynous police, but most of all is the shame women encounter and their unwillingness to talk about it.

So, how can we design something for this problem? How can we get around all these factors and develop something that facilitates the reporting of sexual harassment in public spaces?

After two heavy months of researching and digging into this problem, we were very excited to kick off the conceptualizing phase. But before we started spouting ideas, we went for a small field trip to Singasandra bus stop as a preliminary orientation to give us some more knowledge on Indian public transport. The Singasandra bus stop is due to its location, situated on the route from Bangalore to Electronic City connecting residential areas from the suburbs and outskirts with business and industry from the city centre, a big hub for a highly diverse traveling public. Business men, farmers, commuters, daily workers, salesmen and women, school boys and girls: all people from all ages and backgrounds can be found passing Singasandra on their way towards their destination. Yet, facilities at the bus stop to support this big group of daily travelers are rather poor. Proper safety measurements are missing and neither is it a cozy place where one would come to casually hang out. This bus stop therefore would be interesting for us to have a look at, since all these factors made Singasandra a notorious bus stop in terms of objective and subjective safety.

So off we go!

During an evening rush we spent two hours of only observing the surroundings. It gave us valuable insights in how small groups of passengers behave and how the division of men and women in public transport hubs already becomes significant without it even being forced, like it is in the buses. We also saw that the bus stop is actually designed pretty well, but is improperly used by its travelers, causing the tense unsafe situations.

Enriched with this firsthand experience, we started brainstorming. We resolved to not put any limits to our thoughts. No boundaries, no restraints. Let’s go crazy, let our minds flow freely and see what we can come up with. And so we did. Of course this didn’t guarantee the best or valuable ideas. Haha. No. But it enthused us to exaggerate possibilities into the absurd, going beyond the proverbial box, leaving constraints aside as problems we would take care or get rid of later. Our imagination went in all directions. From silly weapons like an anti-harasser toolkit that will fall from the bus ceiling with inflatable clubs one can bash up the perpetrator with to Twister-like games that boost up the ambience amongst waiting passengers at the bus stop, leaving everybody so occupied and cheerful with the game that no one would even think about harassing the other. Or from a flyover covering poster of a nude woman to distract all the men from the women around him to street tiles, lanterns or bus stop that would alarmingly light up in a certain color if a harassment has taken place in that particular area.

Inspiration and enthusiasm enough. After collecting all the post-its with scribbled down ideas, a rough selection could be made. Like I said before, our aim was to focus on the reporting, that we, due to our enthusiasm, could not always stick to in our brainstorming. Out of the discussions we had on our results, we discovered that a solid concept should contain a collection of data, an incentive for the user to participate, and a feedback of this data towards the bigger public. With these criteria we distilled the three following concepts.

Concept one is a campaign of sorts. At multiple locations in the city, a small counter is located, decorated as a flower kiosk, preferably close to a bus stand. Women who have experienced any kind of sexual harassment at that stand or in the surrounding area can pick up a flower with root, and plant it somewhere at a given open ground behind the kiosk. The more women plant flowers, the bigger the flower bed will grow. It will decorate that specific site of public space, creating a colorful natural palette in the urban environment. But at the same time it will portray an ironic message of each flower representing a woman who has been harassed at that location. As a variation on this idea, the flower kiosk can be replaced by a coffee or tea counter, where people can pick up a free cup of coffee or tea and throw the empty cup in special bins. A green one symbolizing a good personal experience of that particular bus stop (the person feels safe, hasn’t experienced sexual harassment at that site), a red one symbolizing a bad experience (feeling of unsafety, experienced sexual harassment). The fuller the bins, the more data is collected on peoples opinion in terms of that bus stop’s safety.

Concept one is a campaign of sorts. At multiple locations in the city, a small counter is located, decorated as a flower kiosk, preferably close to a bus stand. Women who have experienced any kind of sexual harassment at that stand or in the surrounding area can pick up a flower with root, and plant it somewhere at a given open ground behind the kiosk. The more women plant flowers, the bigger the flower bed will grow. It will decorate that specific site of public space, creating a colorful natural palette in the urban environment. But at the same time it will portray an ironic message of each flower representing a woman who has been harassed at that location. As a variation on this idea, the flower kiosk can be replaced by a coffee or tea counter, where people can pick up a free cup of coffee or tea and throw the empty cup in special bins. A green one symbolizing a good personal experience of that particular bus stop (the person feels safe, hasn’t experienced sexual harassment at that site), a red one symbolizing a bad experience (feeling of unsafety, experienced sexual harassment). The fuller the bins, the more data is collected on peoples opinion in terms of that bus stop’s safety.

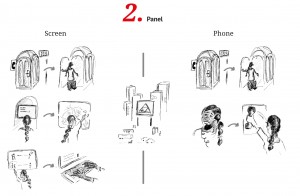

The second concept concerns an electronic panel. Initially we thought of a booth which women can enter and where they can report their case of sexual harassment. The booth can be situated on many different locations trough the city, yet always in a public space, easy accessible for all women. In the booth a number of buttons or touch screen is presented, questioning the woman’s individual cases. For example: the woman is asked, electronically, to give time, location, nature of harassment, identity of perpetrator and herself, etcetera. All this can be presented on a screen, and the woman can answer by pressing the buttons with the corresponding options, or typing on a small keyboard.

The second concept concerns an electronic panel. Initially we thought of a booth which women can enter and where they can report their case of sexual harassment. The booth can be situated on many different locations trough the city, yet always in a public space, easy accessible for all women. In the booth a number of buttons or touch screen is presented, questioning the woman’s individual cases. For example: the woman is asked, electronically, to give time, location, nature of harassment, identity of perpetrator and herself, etcetera. All this can be presented on a screen, and the woman can answer by pressing the buttons with the corresponding options, or typing on a small keyboard.

As a variation on this, the electronic panel on which the questionnaire will be completed can be replaced by an old fashioned phone, which one can take off the hook for talking. The user can now speak about whatever she wants to tell about her case of sexual harassment, and her monologue will be recorded. All the data that is being collected by these booths will be visualized on a big public screen, so a larger audience will now know the status quo of the problem, and users will see that something actually gets done with their data. Aside from this visual feedback via a public screen, the data will also flow to institutions that are dealing with women’s rights and public safety, which they can use for their advocacy.

After the reporting in the booth, the women have the chance to request for a soothing song. Within the booth, a small jukebox will be present, playing the requested song trough the booth. One can choose whether she wants to turn up the volume, sing a long, shout it out, or keep it only hearable for herself. The music played by the jukebox will just serve to offer instant relief or comfort for the woman in the booth, creating a moment for her own, letting her feel better after her bad experience. Other options are a dummy face one can slap or a whack-a-mole kind of possibility to vent frustration.

Another electronic panel-like concept is a change machine. Change, the small denominations of money one gets back after payment with a bigger bill, is a big scarcity in India. Especially in buses for ticket sale. In change of a bill, this parking meter kind of machine at the bus stop would give change, but only after one first answers some questions that will pop up on the panel as soon one activates it. These questions again will be on experienced cases of sexual harassment or the general safety of the concerning bus stand. After this reporting, the panel will ask for suggestions for interventions to change the current (unsafe) situation at that bus stop. So, in order for change, the user should ‘give’ change.

Another electronic panel-like concept is a change machine. Change, the small denominations of money one gets back after payment with a bigger bill, is a big scarcity in India. Especially in buses for ticket sale. In change of a bill, this parking meter kind of machine at the bus stop would give change, but only after one first answers some questions that will pop up on the panel as soon one activates it. These questions again will be on experienced cases of sexual harassment or the general safety of the concerning bus stand. After this reporting, the panel will ask for suggestions for interventions to change the current (unsafe) situation at that bus stop. So, in order for change, the user should ‘give’ change.

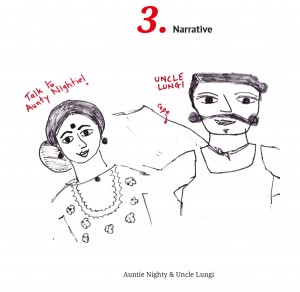

The third concept regards more of a narrative. A set of two colorful cartoon characters, Auntie Nighty and Uncle Lungi, via who’s life and adventures issues like masculinity, sexuality, safety, etcetera are addressed in a playful way. These characters can be the key narrative for a story or game.

The third concept regards more of a narrative. A set of two colorful cartoon characters, Auntie Nighty and Uncle Lungi, via who’s life and adventures issues like masculinity, sexuality, safety, etcetera are addressed in a playful way. These characters can be the key narrative for a story or game.

With these concepts we went for some user testing to win feedback. Around the IIIT-B campus we went for spotting some audience within our target group. Several groups of giggling girls aged between 17 and 25 were asked their opinions about the concepts. And for a second round of interviews we returned to our loyal experts whom we had spoken previously during our research phase. I can tell you that the feedback was pretty spicy and a lot of hidden flaws in our concepts became evident. But bad feedback is the best, so they say, and for us many valuable insights appeared. A professor within IIIT-B kindly pointed us on the fact that a change machine would mean lengthy and difficult negotiations for the banks to cooperate with us and that our chance of succession in this would be minimal. Also, our lovely target group indicated that they would not just take any free coffee or tea from strangers on the street. And yes, that a flower bed in city indeed would be very nice, but what about all the cows strolling around the city streets for which the flowers would mean a delicious meal? Baffled by our own brains that we could not think of these restraints brought by an Indian context ourselves, we had to drop the first set of concepts. Other noteworthy understandings we gained were the delicate balance between guaranteeing full anonymity for the user and the verification of the data, the value of data on the response of the victim, perpetrator, and bystanders on the incident, and the need for solutions or interventions for the problem. Women’s rights organization Vimochana let us see how the problem is already very well known to many people. Defining it again is not necessary, according to them. Instead, provide interventions for it that come from bottom-up.

With our brains buzzing of all the comments, critique and newly gained insights we locked ourselves up again. Time to pick the most promising of our concepts, revise, tweak, and alter it into the mould that appeared out of the loads of feedback. We decided to continue with the electronic panel, for this being a powerful possible tool for the informal reporting. The next steps will be the designing of this panel and all that comes along with it: not only the piece of hardware, but also the system that will run on it, the repository design, data flow, its user interface, the feedback of the information towards the users, you name it. Content, analysis and presentation have to be fully fledged.

So, it seems like we finally shifted away from the Do What? to the What To Do? Keep a close eye on us about more updates on this dazzling design process!