“The goal of VR storytelling is to tell a story that will stimulate emotions that will influence action” – Shin (2017)

In 1980 Marvin Minsky used a term “telepresence” to describe the feeling that a human operator may have while interacting with teleoperation systems. Later, telepresence was translated into “immersion” which generally describes a deep mental involvement in something. During the second sprint we studied immersion in the VR environment, focusing on the process from the users’ perspective. By putting the individual at the centre of the studies about immersion, embodied cognition and the theory of flow we were able to find some new point of views for our topic and get some validations for our concept.

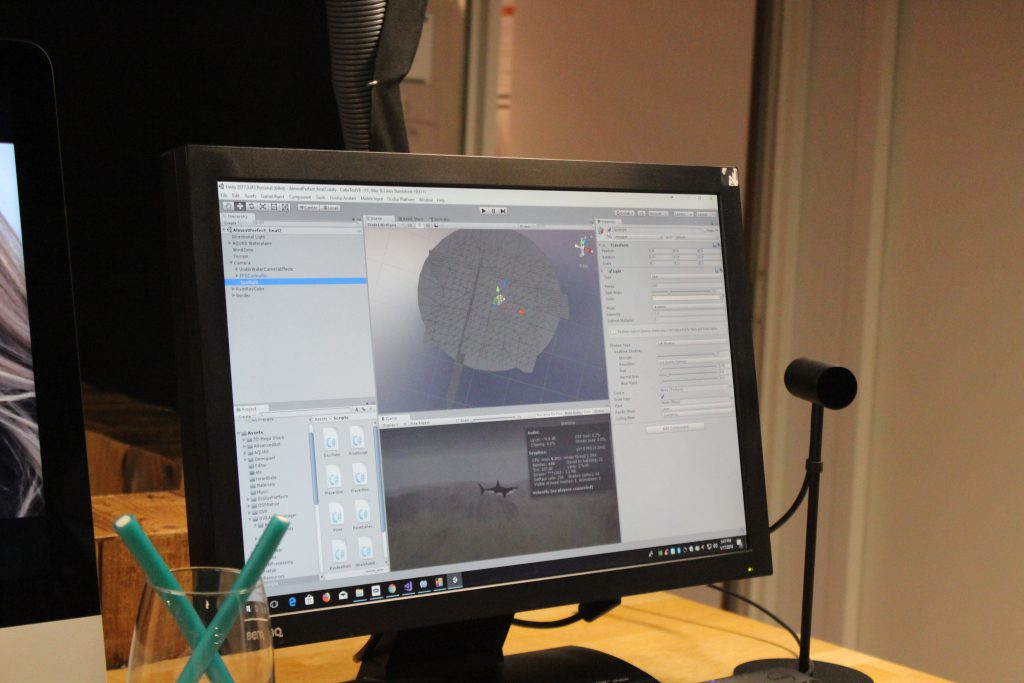

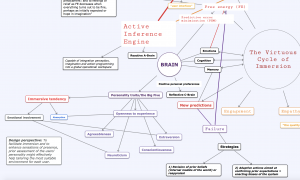

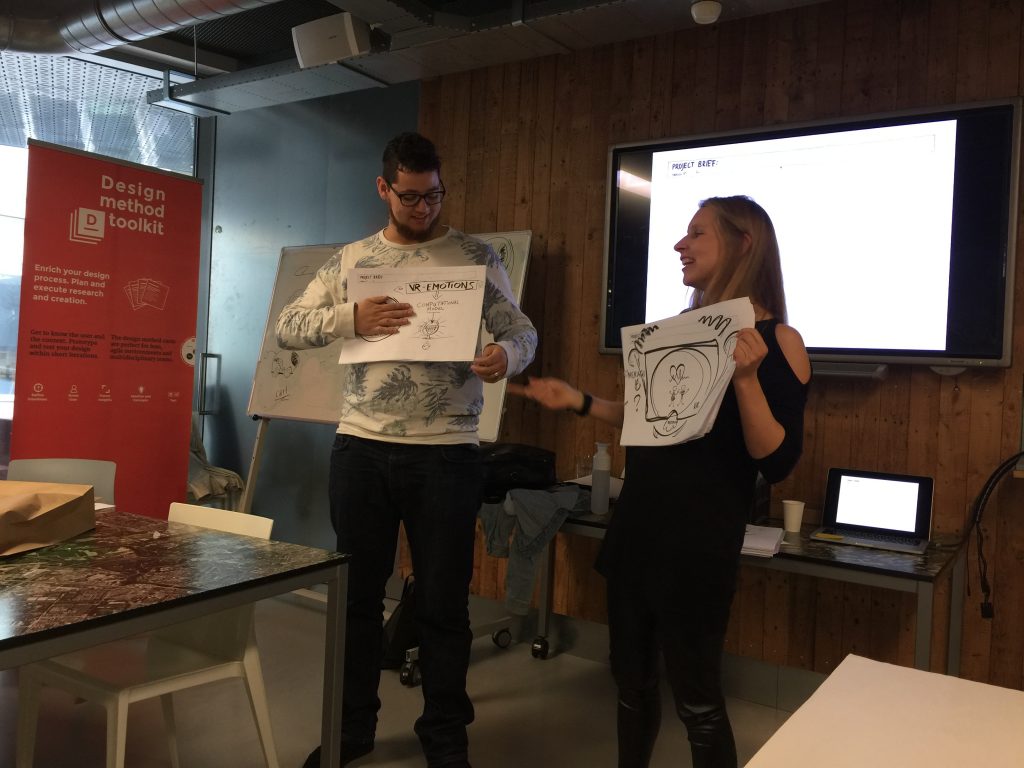

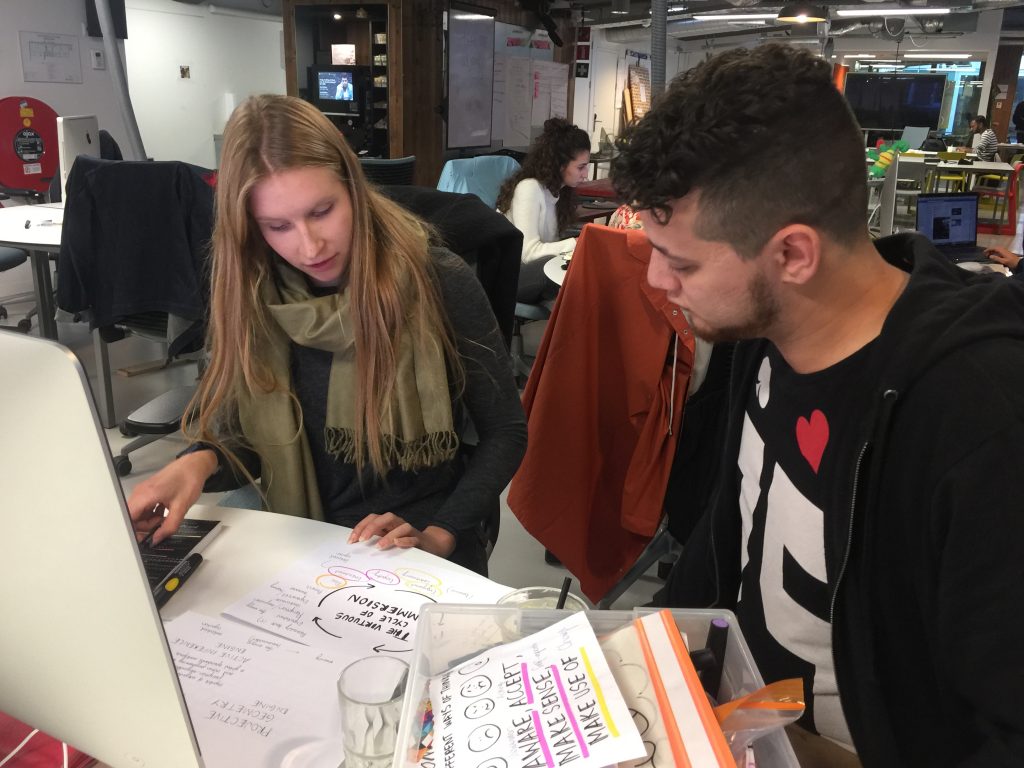

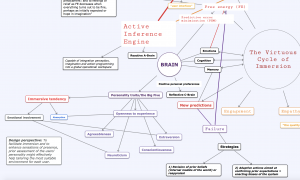

Janina’s physical mind map of “The virtuous cycle of immersion” (aka. never ending story).

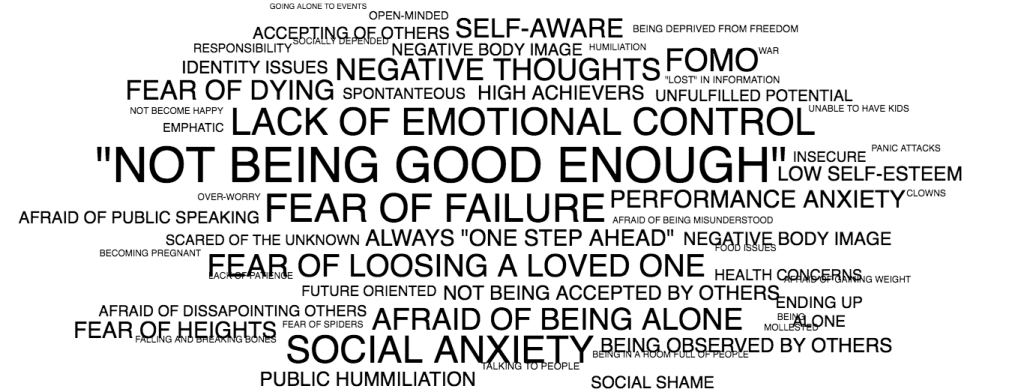

Not surprisingly, the first important notion is again the individuality. The personality traits of the user (the so-called “Big Five”) need to be taken into account before the users’ level of immersion can be analyzed. As Weibel et al. (2010) states, previous studies only show the level of immersion measured in terms of satisfaction and positive feedback of the user, whereas less is left to question how personality traits can influence the overall experience of immersion. Lately, it has been studied that especially some individual factors, such as openness to experience and high imagery ability, have a positive effect on presence – followed up by the immersion (Weibel et al. 2010). During our concept sketching we also faced this problem and we found ourselves asking what motivates our target group. What make the 15 to 24 year old women to get up from bed every morning?

Figure 1. A screenshot of Janina’s mind map (which is as fluid as the concept of immersion by itself). With the help of this map, we are able to see that in addition to “openness to experience” also emotional involvement of the user might be relevant for the level of immersion. And as you can see, the design perspective states that in order “to facilitate immersion and to enhance sensations of presence, prior assessment of the users’ personality might effectively help tailoring the most suitable environment for each user” (Weibel et al. 2010).

In addition to the personality traits of each user, the notion of body and the sense of embodiment are important for defining the level of immersion. The VR environment not only make users to feel different kind of emotions but moreover changes who they are in the virtual space (Shin 2017). Fully immersive VR environment offers a sense of embodiment, which can be defined as a state where the users feel themselves as a part of the VR environment. At the same time, users can also feel that VR components are parts of their own bodies (see Bailey et al. 2016). In fact, the users often create a virtual body of themselves inside of the immersive VR environment as “an analog of his or her own biological body” (Kliteni et al. 2012).

“In other words, the embodied cognition in VR allows users to feel a sense of embodiment.” (Shin & Biocca 2017)

As Shin and Biocca (2017) conclude, this sense of embodiment comes from our embodied cognition which we process by being physically “present” somewhere. Marvin Minsky (2006) would probably include presence as one of those suitcase-like words, which doesn’t have a clear definition but which can help us to understand our brain processes. However, we will define presence for now as a state of mind and immersion as an experience over time (Shin 2017). In fact, presence is not unique for the VR as also watching a movie or simply reading a text can induce a feeling of presence (Baus and Bouchard 2014). However, presence and immersion together are both strongly related to our ability of perspective taking and perception (Rudrauf at al. 2017).

If the immersion in the VR environment is defined as “an experience over time” and not an instant temporary connection (which we would probably call a presence), it means that the user’s cognition is highly involved to this process. The VR environment, as well as the stories told in VR, are constantly reprocessed through the user’s sense-making. As Shin (2017) argues, “users actively create their own VR, based on their understanding of the story, their empathetic traits, and the nature of the medium.” Therefore, the role of VR developers is only to propose an immersion but the processing of the immersion is left for the user. It is important to understand both presence and immersion as fluid states that are reprocessed and redefined by the user. (Shin 2017.)

Some other necessary elements for immersion and the engagement of the user are the ability of perspective taking, the concept of flow and empathy. Of course, the ability of perspective taking involves the 360 degree nature of the VR environment. Unlike in other mediums, in virtual reality the user is not limited to 2D perspective taking and perception, but allowed to all kind of projective transformations (see the mathematical model of embodied cognition by Rudrauf at al. 2017). This can also mean that in some scenarios less is left for the imagination, as the user is given the ability to observe the VR environment from every angle before making predictions. In comparison, TV screen as a medium forces us constantly and unconsciously to take into account those invisible cues framed out of the screen – and filling them in with our own imagination.

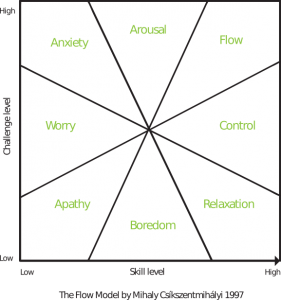

The concept of flow is said to be a determining feature for the ability to emphasize and embody VR stories (Shin 2017). First of all, it can be argued that immersive technology and VR produce empathy only because of the sense of embodiment – it places the user in the centre of the experience. However, Shin (2017) also differentiates presence and flow from each other stating that “Presence can be immersion into a virtual space, whereas flow can be an experience of immersion into a certain user action.” Flow, in this context, always involves action.

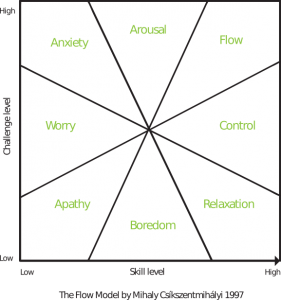

Figure 2. The Flow Model of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1997). As we see, the arousal level is in between the anxiety/fear and the state of flow. This figure partly follows the Russell’s circumplex model of affect (1980).

The common view is that breaks in presence (BIPs) need to be avoided in order to keep up the immersion of the user in the VR environment. Slater and Steed (2000) were first to define the concept of BIP, describing any event whereby the real world becomes apparent for the participant. However, this feature could be further studied with our topic related to different kind of phobias and their treatment. Would it be possible to play with the breaks in presence in order to help people to conquer their fears? In fact, some exposure therapist argue that for some phobias the distraction might hinder the process whereas for other it might actually work as a facilitating feature (McNally 2007).

We also took a look at calm technology and how it could be relevant for the level of immersion. Of course, the immersive experience needs to be mediated as transparently as possible, without the technological interference becoming an obstacle for the user. For people having a low immersive tendency all the technological aspects probably need to be more carefully designed, but as the previous studies show, the technological aspects by themselves are not the main ingredients for the immersion. (Weibel et al. 2010; Shin 2017.)

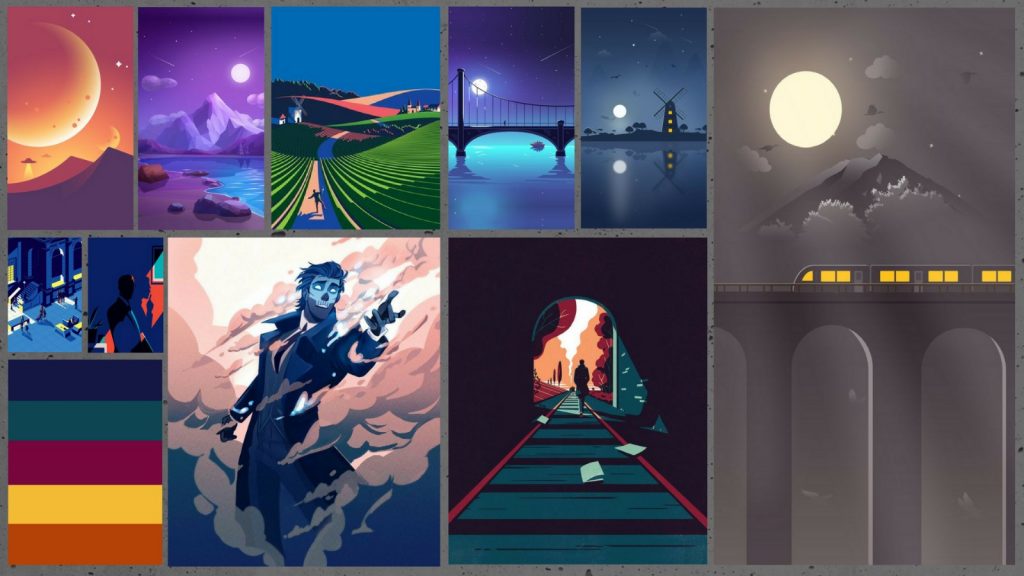

One popular point of view for the definition of immersion is the coherency of the environment. This means that the VR environment doesn’t necessarily need to follow the common laws of physics, as long as it follows some kind of coherent laws and rules. This feature proficiently implemented to virtual reality can surely turn out to be beneficial in some cases, and is something we will try to keep in our mind.

As Shin (2017) concludes:

“Future research should see immersion as a cognitive dimension alongside consciousness, awareness, understanding, empathizing, embodying, and contextualizing, which helps users understand the content and stories delivered.”

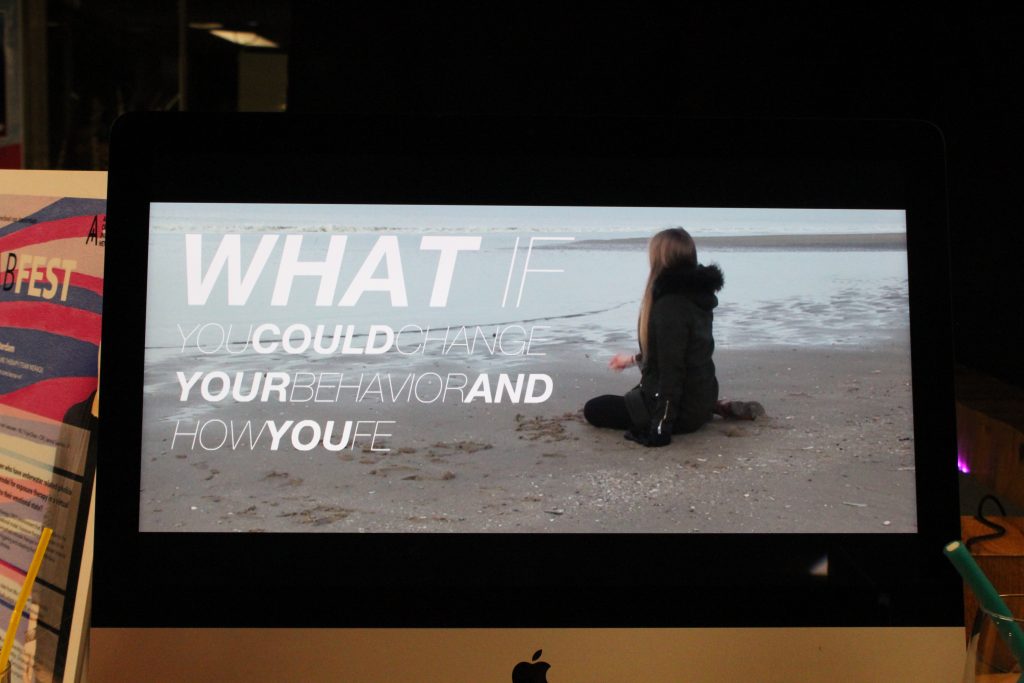

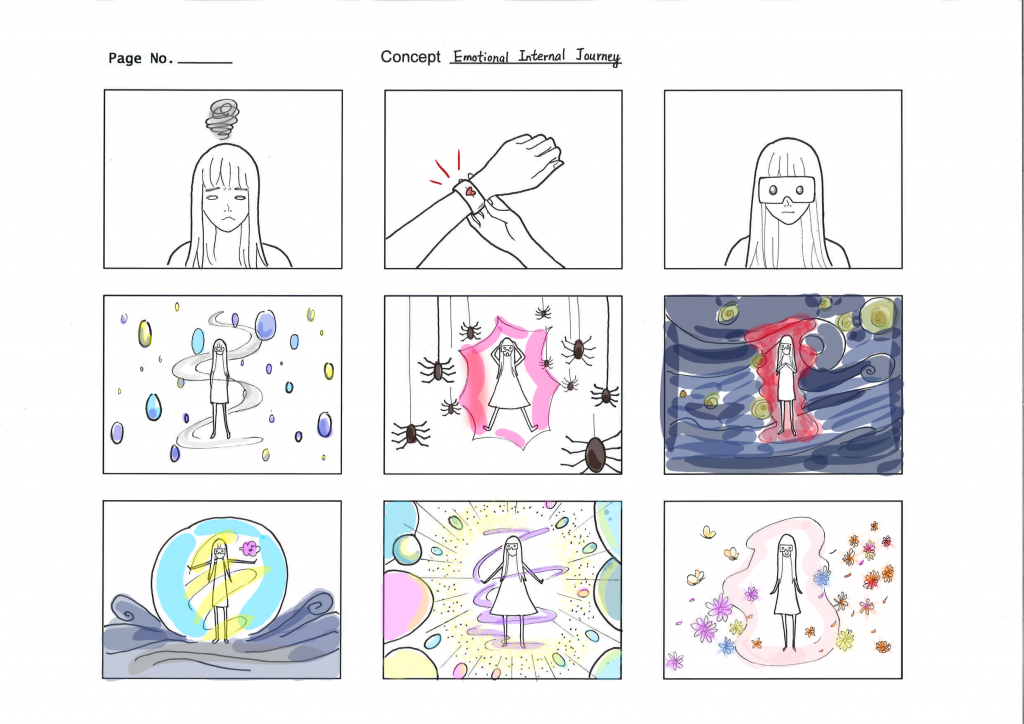

Understanding the concept of immersion is important for us as we are working on with different kind of phobias and fears, focusing on their treatment with exposure therapy in VR. As the main challenge is to change the fear memory of the user, the VR environment needs to be immersive and realistic enough in order to implement the behavioral change of the users also in vivo – in other words – having a long term impact.

Next, by taking a deeper look into those different kind of levels of our consciousness (ie. trying to make sense of Minsky’s theories), and searching for all types of relative “black holes” for our emotional processing we still hope to find new insights for the emotion recognition during the coming sprints.

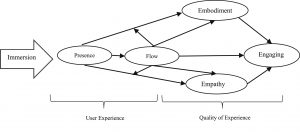

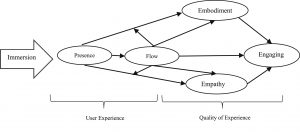

Figure 3. One proposed model of immersion with the levels of user experience and the quality of the experience (Shin 2017). We find this model too simple to define all the aspects of immersion but it well states the sense of embodiment and empathy as guaranteeing the quality of user experience in VR environments. Baus and Bouchard (2014) also name three aspects from where to measure the quality of the user’s experience in VR: the feeling of presence, the level of realism and the degree of reality.

Sources:

Bailey J., Bailenson J., and Casasanto D. (2016). “When does virtual embodiment change our minds?” Presence. Vol 25(3): 222-23

Baus O. and Bouchard S. (2014). “Moving from Virtual Reality Exposure-Based Therapy to Augmented Reality Exposure-Based Therapy: A Review” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. Vol 8: 112.

Kliteni K., Groten R. & Slater M. (2012). “The sense of embodiment in virtual reality”. Presence 21(4): 373–387.

McNally R. (2007). “Mechanism of exposure therapy: How neuroscience can improve physiological treatments for anxiety disorders” Department of

Minsky, M. (2006). The Emotion Machine. Commonsense Thinking, Artificial Intelligence, and the Future of Human Mind. Simon & Schuster, NY.

Rudrauf D., Bennequin D., Granic I., Landini G., Fristoni K., and Williford K. (2017). “A mathematical model of embodied consciousness” Journal of Theoretical Biology. Vol. 428:106-131

Shin, D. (2017). “Empathy and embodied experience in virtual reality environment: To what extent can virtual reality stimulate empathy and embodied experience?”. Coming in Computers in Human Behavior, January 2018, Vol.78: 64-73 Available online:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563217305381

Shin, D. & Biocca F. (2017). “Exploring immersive experience in journalism”. New Media & Society. September 30, 2017

Slater M. and Steed A. (2000). “A virtual presence counter” Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments. Vol 9(5):413–434

Weibel D., Wissmath B. & Mast F. (2010). “Immersion in Mediated Environments: The Role of Personality Traits” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. Vol 13(3): 251-256.