With each passing week our project seems to become timelier. It’s quite a strange situation. You always want to work on societally relevant topics, but the relevance of our project is unfortunately exacerbated by the horrific events of the last couple of weeks. The refugee crisis is destabilizing the Balkan region to a worrying degree. Angela Merkel warned a couple of weeks ago that she fears for renewed conflicts in the region if Germany closes its borders. That seems for now to be a bit of an overreaction, born out of a sense of urgency. Nevertheless it is a fact that tensions among former Yugoslav states are rising, especially because some of these nations are now EU-members, while others are not. For a while the borders between Slovenia, Croatia and Serbia were closed, something that wasn’t even the case during the wars in the 1990’s. And in of the more ironic developments of the last month, Macedonia decided to build a fence along its border with Greece.

Still, we should not forget that it are the refugees who are most affected by this crisis, not the nations taking them in. We saw two weeks ago in Paris what kind of violence they are fleeing from. The attacks don’t need to be discussed much further. They were awful and tragic. Hopefully the survivors and the families of the victims will be able to someday move on. The aftermath of the attacks is more interesting to address, especially in the context of our project.

The impact of the Paris attacks was easily noticeable. Facebook users overlaid the French flag over their profile pictures. The national media rearranged their schedule to focus on the events in Paris. Soon, this attitude of collective mourning was heavily criticized. One day before Paris, ISIS had killed 46 in Beirut. Why did no one incorporate the Lebanese flag in their Facebook profile picture? Why wasn’t the television news rearranged for Beirut? Do we only care about international terrorism when westerners are victims?

These questions are to some extent fair. We have criticized the western Orientalist attitudes before on this blog. For centuries the Arab world has been presented as inferior to the west. That has certainly shaped ordinary people’s preconceptions of it. These preconceptions cannot be reversed by writing a couple of critical tweets or news articles after a terrorist attack, and then forgetting about the nation until the next time something awful happens. To change these attitudes you need reporting, outside the context of terrorism, which focuses on ordinary life in Lebanon, and on the nation’s culture and history. In other words, as one commenter wonderfully summarized ‘before caring about dead Arabs, we must first care about living Arabs”. In the meantime many will genuinely be more affected by French victims than by Lebanese victims. Forcing them to feel otherwise is fruitless, and possibly even counterproductive.

The way people reflect can be guided a bit, but it cannot be controlled or measured. That’s probably the biggest problem we are faced with in our project. We cannot really know how well the tools we create work, no matter how many questionnaires our participants fill in. Furthermore our tool does not necessarily need to have an immediate effect on our users. They may not reflect right after using our tool, but when going to sleep, or the next time when they talk to someone from another nation.

What we can do is create more diverse tools that trigger reflection in different ways. To that end we organized a test session with some of our friends at MediaLab. We gathered six people and first asked them to answer a simple question: “What makes you reflect?” They produced many sticky notes with very interesting, varying answers. The classics, like showering, and looking out of a train window, were also invoked. Other interesting answers included road trips, smells, movies, buildings, the breaking of routine, and other people’s stories. After this, we asked them to think of interesting reflective activities/installations that could be used in an exhibition. Again their ideas were very interesting and helpful. Our colleagues like quiet spaces with reflective sounds and images. They also like recreating specific memories, through games, drawings or discussion. Simulating reality, talking with people about their experiences, and having to answer questions were other interesting suggestions.

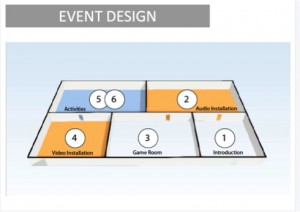

We combined our peer’s ideas with some of our own to create a prototype for an exhibition. The exhibition is called for now Six Spaces, the idea being that there is one space for each of the six former Yugoslav republics. For now, the exhibition is intended as a one-time event that will most like find its audience at a university, community center, or educational center in the region. Hopefully it can take place in each of the six nations. These ideas are currently very much in their first stages of conception though. For them to have any chance of becoming reality, we have to first find some organizations in the region that would be willing to host/co-organize it. And once we have found them they have to of course approve of our ideas. We may take some steps in that direction on Monday, when we will have a Skype interview with an employee of the Youtb Intitiative for Human Rights (YIHR).

In one of the spaces of the exhibition visitors can play the Ghost of Tito. Furthermore there will be a space with a video installation, one with an audio installation, and a space called the The Diversity of Thought Room. The space with the audio installation is a mostly darkened room, with five different ‘stations’ where an audio outlet is connected to a so-called Littlebit. The Littlebit is a device very similar to the Touchboard discussed in the previous post. The Littlebit can be programmed in such a way that when it’s lit up, with a smartphone for example, it will play sounds. In our audio room each Littlebit is connected to sounds of war, witness accounts, or news reports.

We have created a prototype of a video that can play on a loop in the video installation room. It is based on the fact that after the dissolution of Yugoslavia, and during the wars, Yugoslavia’s successor states created nationalistic narratives in which they presented themselves as different from each other, and from Yugoslavia as a whole. Propaganda played a vital role in the creation of these narratives. Our video intends to blur Bosniak, Croatian and Serbian propaganda to such As such in the video, propaganda images are used to expose the similarities between the nations, rather than their differences. In doing so, the propaganda images are repurposed and re-contextualized, and because of that the propaganda perhaps loses some of its power. an extent that it becomes hard to discern what nation the footage is connected to.

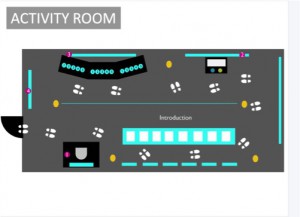

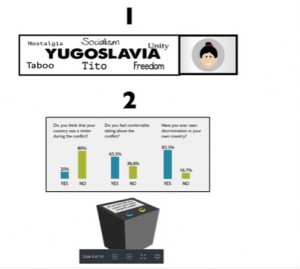

The Diversity of Thought Room consists of four activities and an introduction where (the importance of) diversity and respect for different cultures is discussed. The introduction comes after the first activity though, which is a word association game. Through an interactive installation the vistitors will be asked to describe with just on word, another term, object or place. Later on in the room you will be able to see a word cloud of all the different answers.

After the introduction, comes the second activity where visitors will be asked to answer closed questions. On a screen you will be able to see how the answers have been distributed. The third activity is another interactive installation. Three vsitors have to choose among five images, the image they feel describes best the word that appears on screen. The last activity is an app allowing visitors to share their opinions and ideas. A screen will show a live-feed of their comments.